The Blind Box Playbook For Founders And How To Use It For Good (Part 2/2)

POP MART proved that people love the thrill of the unknown. In this second part of the series, we explore how blind-box mechanics in other industries and lessons we draw as founders.

Happy Friday!

This is part two of the series. In part one, we looked at how POP MART turned uncertainty into a billion-dollar company in just ten years.

The mechanics of the blind box, the psychology of randomness, and the theatre of unboxing created a cultural phenomenon that, I have to say, my wife and I fell into ourselves. Last week’s piece was as much a personal confession as it was an exploration of why it worked so well on us.

But POP MART isn’t an outlier. Blind-box mechanics appear everywhere once you start looking. Some industries use them to delight (what I call the “light side”). Others exploit the psychology and drift into manipulation (the “dark side”). The real lesson for founders is how to adapt this responsibly: creating products people chase for joy, not out of compulsion.

So this week, let’s write the playbook of the blind box.

If someone forwarded this to you, it’s time to subscribe.

Blind Boxes Beyond Toys

Trading cards are the most obvious cousin and the closest to me personally. Pokémon and Magic: The Gathering built empires on packs with a slim chance of pulling a rare card. The “chase” card can be worth hundreds or thousands of dollars, which keeps collectors buying pack after pack. In 2023, Post Malone famously bought one of these cards for $2 million. Just like Labubu, the unboxing content for trading card games have become a huge genre in themselves.

Video games leaned heavily on the same psychology. New skins for your characters, rare items hidden in loot boxes, the random friend or foe you encounter in the weeds. The reveal moment is everywhere in gaming.

Sneakers are another clear example. Nike scaled it with their SNKRS app, which gives you a chance to get one of their daily drops. Another blind box in semi-disguise.

And finally, crypto and NFTs. At the peak of the hype cycle, randomised minting and rarity levels created million-dollar sales overnight. Here again, the mechanics were the same.

The Dark Side 🌑

Not all blind boxes end well.

Loot boxes in gaming became a cautionary tale. While researching this article I came across stories of children in the UK draining their parents’ bank accounts through Nintendo Switch online games. What began as a way to inject excitement turned into accusations of predatory monetisation. Several countries have since introduced restrictions.

Randomness can hook people in the short term but erode trust in the long term if used cynically (and may soon face regulatory scrutiny). The line between delight and exploitation is much thinner than it looks.

The Light Side 🌕

Surprise doesn’t have to be manipulative. Done right, it can become one of the most powerful tools a founder has.

Think of the unexpected delight when a brand drops a limited-edition design. Or when your favourite app finally launches a much-wanted feature. Or the small spark of joy when you stumble on a hidden product Easter egg. These are all delightful blind-box moments.

The litmus test 🌓

So how do you know if your blind-box mechanic sits on the light or the dark side?

The answer has to come from both the customer’s experience and the product owner’s intent.

On the light side, the surprise creates delight without debt. Customers enjoy the reveal, but they feel free to walk away. The mechanic supports curiosity, not compulsion. It adds joy without taking control.

On the dark side, the surprise preys on compulsion. Customers overspend, feel regret, or lose track of how much they’ve invested. Even if they don’t admit it, the design is built to exploit addiction.

A founder’s responsibility is to ask:

Am I designing for joy, or for dependency?

If I plotted my users’ long-term wellbeing, would this mechanic leave them happier, or more depleted?

Would I want my own child, partner, or friend using this product daily?

When in doubt, listen less to how excited a user looks in the moment and more to the emotional toll over time. Addiction feels like joy in the short term, but it’s the designer’s job to know the difference. At least that’s my point of view.

The Founder’s Playbook

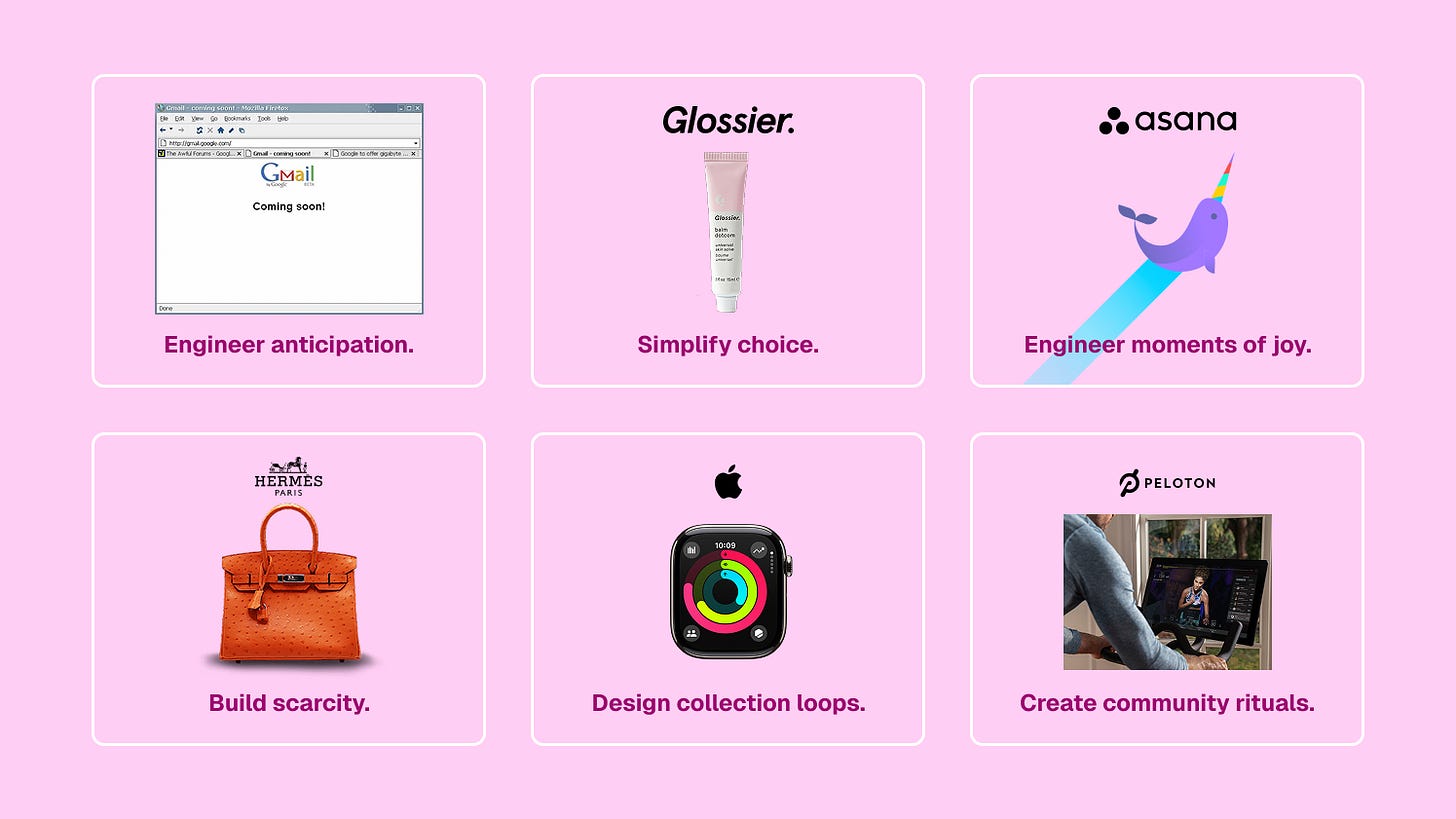

Here are a few principles, paired with real-world examples of companies that leaned to the “light side”.

Engineer anticipation. POP MART has new collaborations. Gmail did it with exclusive invites and slow rollouts.

Simplify choice. POP MART collapses multiple options into one. Glossier offered only four products at launch.

Engineer moments of joy. POP MART has the foil-bag reveal. Asana has quirky creature animations when you finish tasks.

Build scarcity. POP MART has chase characters. Hermès has the Birkin bag.

Design collection loops. POP MART has collection sets. Apple Watch has completion streaks.

Create community rituals. POP MART has swap events. Peloton has live classes.

The thrill doesn’t have to be tied to gambling mechanics. Ask yourself: does this mechanic make my customer happier or just more dependent?

The blind-box effect can be engineered to drive desire, but your product still has to deliver.

Closing the Series

Blind boxes prove something counter-intuitive: people crave the thrill of the unknown, provided it’s wrapped in theatre, community and design.

As we’ve seen in this series, POP MART and others built empires on the mystery inside a box. The lesson for founders is not whether to use uncertainty, but how. Done responsibly, it can transform ordinary products into experiences people talk about, share, and remember.

Now I’m curious: what blind-box strategies have you seen or even used yourself? And on which side did you land, 🌕 or 🌑 or 🌓?

Thanks for reading.

There is no road.

The road is made by walking.

— Thomas