The Psychology Behind POP MART’s success (Part 1/2)

POP MART turned uncertainty into a billion-dollar business. Here’s how blind boxes, Labubu and the psychology of randomness created one of the smartest recent consumer playbooks.

Happy Friday!

Today I’m writing in a slightly different format than my usual articles. That’s because I’m starting a two-part series on the crazy success of POP MART and the iconic characters of Labubu.

If someone told you, “You can buy this box but I can’t tell you what’s inside,” it would sound absurd. Yet that’s the exact proposition at the heart of POP MART’s success. For anyone who has never heard of them, the concept is simple: you buy a sealed box with a figurine inside, and you only know what you’ve got after opening it.

POP MART is not the first example of the “blind box”. In many ways it’s a toy version of Storage Wars.

This got me so curious that I set aside time to study it and write down the key learnings I found. Why do we pay so much for blind boxes? And how does POP MART turn uncertainty into their main feature, while most businesses try to remove it?

So here it is. Part One.

If someone forwarded this to you, it’s time to subscribe.

POP MART sells uncertainty

POP MART has become a billion-dollar empire on the back of a paradox: we love buying what we don’t know. Customers queue for hours, trade chase figurines, and post their live unboxing reactions to audiences eager to share the thrill.

Why does something that looks like gambling dressed up as toys work so well? As we will see, it’s one of the smartest lessons in choice architecture and consumer psychology I’ve ever seen.

The Origins of the Blind Box

Blind boxes aren’t new. Japan pioneered them in the 1970s with Gashapon machines, capsule toys sold at random through vending machines. Even earlier, baseball cards in the 1950s introduced the “chase” card: a rare insert that made children, and plenty of adults, buy pack after pack.

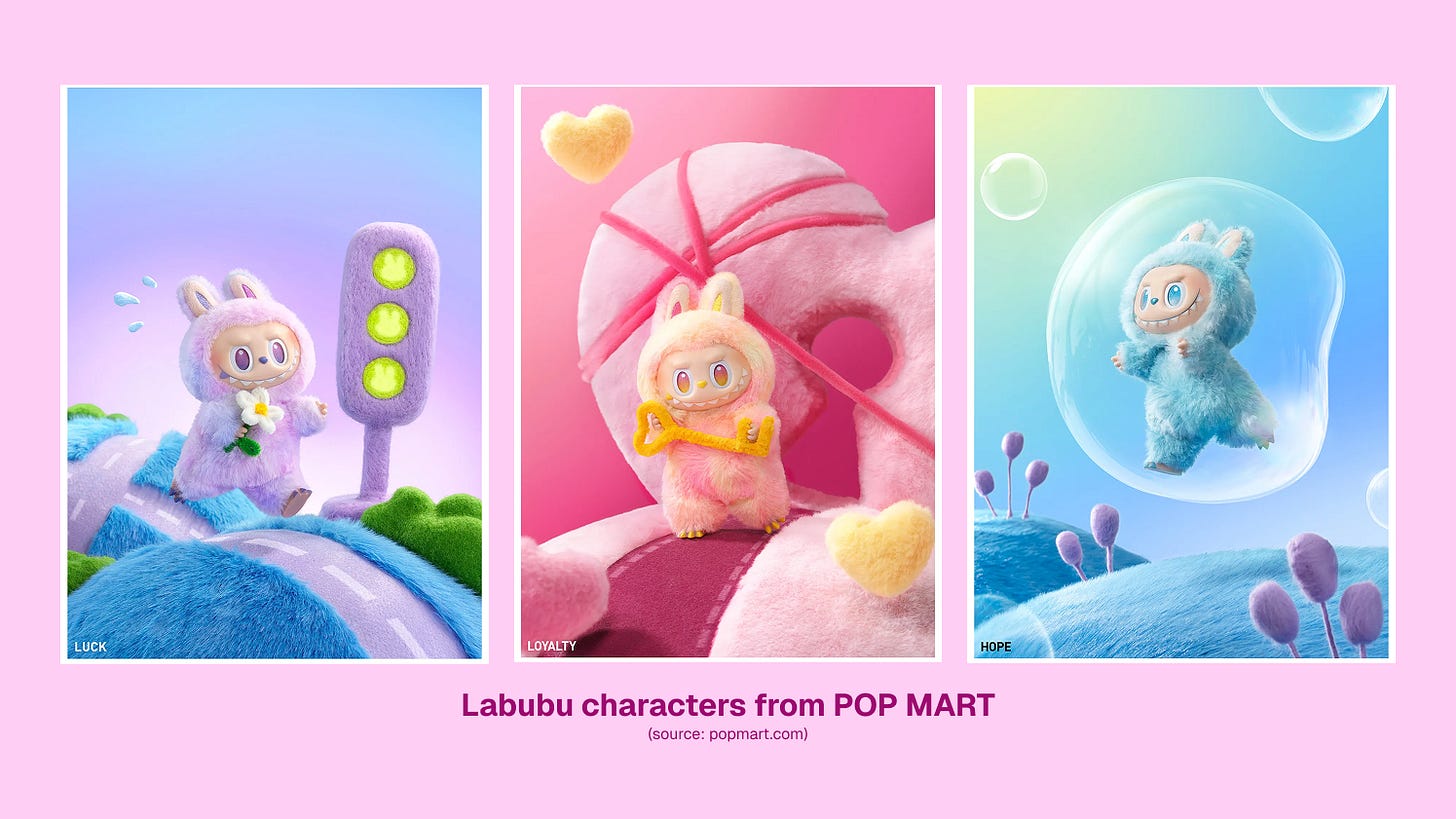

POP MART entered the scene in Beijing in 2010 as a lifestyle and design retailer. The breakthrough came in 2016 with a figurine called Molly, designed by Hong Kong artist Kenny Wong. The blind-box format took off in China’s millennial and Gen Z culture, blending collectability with fashion sensibilities.

By 2020, POP MART went public in Hong Kong at a valuation of seven billion dollars. Today, they operate hundreds of stores, vending machines across Asia, global collaborations with Disney, Coca-Cola, One Piece and Harry Potter, and are even building theme parks (the first is called POPLAND). The “art toy” category they helped professionalise is projected to hit forty billion dollars by 2030 in Asia alone.

All from selling boxes you can’t see inside.

The Mechanics of POP MART’s Blind Boxes

At first glance, the blind box looks simple: one sealed box, one figurine inside. But the system has been designed with a precision any founder should study. You’re not asked to choose between different figurines, you’re asked to make one decision only: buy the box or walk away. The paradox of choice disappears and the purchase becomes an instinctive yes or no.

Each series is structured around scarcity. Most figurines are common, but one or two are “chase” editions. The odds of getting them are usually one in seventy-two or worse. It’s rare enough to drive repeat buying, but just plausible enough to keep your hopes up. The odds are no secret, they are directly printed on the box. Everyone knows it’s a gamble.

The figurines are released in sets, often of twelve, which means that after buying a few, you feel as if you’ve only just started. The collection design creates a sense of unfinished business, amplified by the ritual of the unboxing itself.

POP MART wraps all this in physical theatre. Their stores are designed as stages to make the purchase part of the ritual. And because they release new series and collaborations constantly, there’s always another loop waiting to be entered.

The Psychology of Randomness

The mechanics are only the stage. The real story happens in the brain. And there are many psychological reasons why we keep going for more Labubus.

Randomised rewards have been studied since B. F. Skinner’s experiments on pigeons in the 1930s. When rewards arrive on a variable schedule, dopamine spikes are higher than when they are predictable. The same principle keeps gamblers glued to slot machines, and in the case of POP MART, it keeps collectors coming back for another blind box.

Once you start a collection, you experience what psychologists call the endowed progress effect. Ownership creates a sense of obligation to finish. It’s as if not completing the set was a kind of loss. Related to this is the Zeigarnik effect: unfinished tasks create tension the brain wants to resolve. Ten Labubu figurines out of twelve feel less like success and more like an itch you can’t quite scratch.

Blind boxes also offer decision relief. We dislike complicated choices, and POP MART elegantly sidesteps that problem by collapsing twelve different products into one purchase decision. You buy the box and accept the surprise. It’s oddly comforting.

The POP MART recipe for getting you hooked on buying is almost complete. Add in fear of missing out and the social signalling of the rare chase figurine, and the cycle is locked in.

But can it last forever?

Novelty has a half-life. If every box feels the same, fatigue sets in. POP MART knows this, which is why they launch new intellectual properties like Dimoo, Skullpanda and Labubu, collaborate with franchises, and constantly redesign the theatre of the purchase.

Marketing as Theatre

POP MART choreographs the entire customer experience. Each box is beautifully illustrated, and inside is a sealed foil bag that doubles the suspense. Every detail reinforces the drama of the reveal.

They also fuel the community. Fans collect, trade, swap, display and share. POP MART leans into this by hosting official swap events and cultivating fan groups. A figurine becomes more than a product; it’s an invitation to a larger community.

And crucially, POP MART tells stories. Their characters have backstories and worlds. Labubu isn’t just a toy with big eyes and strange charm; he belongs to a universe you can step into. Retail becomes stagecraft. Stores and vending machines are designed as immersive sets, making the act of purchase feel closer to performance art than to shopping.

Closing Part 1

POP MART has built one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer businesses by making uncertainty the star of the show.

Next week in Part Two, we’ll explore how blind-box mechanics show up in trading cards, gaming, sneakers and subscription boxes. We’ll also talk about the dark side when surprise becomes exploitation, and how founders can ethically engineer moments of joy in their own products.

Because uncertainty is a powerful tool. The question is: will you use it to delight, or to exploit?

Thanks for reading.

There is no road.

The road is made by walking.

— Thomas

loving this!